More family tales, triumphs, tears, tribulations:

facts, oddments and incidents

from the lives of our family members. Some funny, some sad, some just

astonishing, some mildly interesting. But all very true. A confused jumble

or medley of things ...

Mesmerism and the Seventh Son

The Victorians toyed with Mesmerism for medical uses.

Mesmerism was developed from the 18th century work of Franz Mesmer, who maintained that illness was caused by blockages in the natural flow of a universal vital energy throughout the human body. Harmony could be restored by various techniques including hypnotism and laying on of hands. It was a technique that was widely adopted in the mid-nineteenth century. Capern was a Devon mesmerist who worked in Tiverton and became Secretary and Resident Superintendent of the Mesmeric Infirmary at Bloomsbury in London.

When he was in his early 60s Samuel Chudleigh was seized with pains all over his body. The doctor of the union attended him, but without any benefit. In a fortnight, his condition having deteriorated, he was admitted to the Exeter Hospital. While there he continued getting worse, and at the end of a fortnight requested to be sent home, as he thought he should die if he stayed any longer. Capern continues the account. "He was conveyed home with great difficulty, and was then confined to his bed for a year and ten months. He was again attended by the union surgeon, who, however, did him no good: indeed, often told him that his case was hopeless. During this time he suffered great pain: his legs and arms became contracted, and he felt as if they were chained together; and, the disease attacking his eyes, he lost the sight of the right. At the end of that time, however, he improved a little, and was able to leave his bed. His legs still remained contracted, and he was quite unable to move without crutches. In that state he remained for three years more, when his son, who resided at Tiverton, advised him to apply to Mr. Capern. He accordingly came to Tiverton, a distance of sixteen miles, and on the 26th February Mr. Capern mesmerised him for the first time. He felt considerable warmth in the limbs, and slept better that night than he had ever done since he was first ill. After six mesmerisations he was able to walk without crutches, and go up and down stairs in the ordinary manner." Although his limbs were still contracted, he was able to walk without any inconvenience. He was full of gratitude for Capern's treatment.

According to Capern, a remarkable fact about this patient was that he had been practising "mesmerism" unknowingly from the day of his birth. "A popular superstition exists in Devonshire that every seventh son possesses the power of curing disease by the simple application of the hand. So firmly is this believed that persons were waiting anxiously for his birth in order to be touched by the new-born infant, should it be a boy, for the cure of their diseases." Apparently Samuel had been practising his power every Sunday, the day of the week on which he was born. He would think on a specific quote from Scripture while making seven passes over the diseased part of his patient "precisely in the mode adopted by mesmerists, decreasing the number of passes every Sunday by one until he comes to the last; always, however, taking the same time in making each lesser number of passes that he had previously taken in making the seven, so that the one pass on the seventh Sunday occupies as much time as the seven passes did on the first." If the "treatment" had not been successful by the seventh Sunday, then the process was repeated for another seven weeks.

During his stay in Tiverton, whilst under Mr. Capern, he was visited every Sunday by persons suffering from scrofula, on whom he operated in his usual manner. "Two of these, Mr. Upton, of Bickleigh, and Mr. Clarke, declare themselves much benefitted, and I allude to their cases as they came under my own observation. " His father, also supposedly a seventh son, practised the cure of disease in the same manner: Samuel was believed to possess extraordinary powers of healing because he was the seventh son of a seventh son. As well as his "mesmerism" passes, a sixpence or other piece of silver would be sewn into a small bag, and that bag into a second, and this charm worn around Samuel's neck during the seven weeks. It was then given to the patient, who would wears it for the next seven weeks, and it was afterwards deposited in a box to be carefully preserved from wet or the touch of a needle, less the disease should return.

Unfortunately extensive research has revealed that Samuel was sixth of eight sons, or fifth of seven surviving sons. Though no suitable alternative candidates for Capern's patient of that name and age have been found, so it seems certain that our Heard family Samuel is the subject of Capern's account.

Mesmerism was short-lived. Its most celebrated British exponent Professor John Elliotson, who had founded the Mesmeric Infirmary, had earlier been one of the founders of University College, London. But in time Mesmerism fell into disrepute, and with it the reputation of Elliotson. He was ousted from UCH, but continued to practice despite widespread opposition to Mesmerism in the Medical Establishment.

Our Wright 'cousin', the Piggoreet Murder and Victorian CSI

Thomas Burke was an Irish migrant who arrived during the Victorian gold rush, moving first to Melbourne where he worked for the Bank of Australasia, before becoming manager of the Smythesdale branch of the bank around 1860. Smythesdale in the 1860s was a prosperous gold-mining town, about 12 miles west of Ballarat. One of Burke's tasks as bank manager was to travel throughout the diggings buying gold from miners. By this stage gold transports were not accompanied by armed escorts. Early on 10 May 1867, Burke collected a horse and buggy from the Smythesdale coach-builder and traveled to the Break O’ Day area (now Corindhap, Victoria), arriving at the nearby town of Rokewood at 11.30 am. He bought gold at Rokewood and Break O’ Day, then left to make the return journey to Smythesdale, stopping at hotels along the way to buy more gold.

Thomas Ulrick Burke.

A number of people saw two men riding fiercely across country. This seems to have raised suspicions when the murder of Burke was announced. They were also seen by other witnesses a few minutes before the murder must have taken place, in the locality where the body was found. The witnesses were able to describe the men and more particularly their horses, a black mare and a bay. If the murder had never occurred, inquiry would naturally have been prompted as to what business men making such an expedition were up to there. Armed with the witness statements, investigations by the police led them to Searle and Ballan, and their horses. The two men were arrested on suspicion of murder. Neither would confess.

On the day of the murder the suspects had two horses shod by one Tigland Morrissey. The suspects' horses were taken to our family member blacksmith George Neville, and observed by Inspector Stoney, George removed the shoes from the horses, taking care not remove the nails from the holes. Native Australian trackers examined the murder scene and the environs with the police. A careful examination of the tracks traced there was made, and they were found to fit exactly, and bear all peculiarities of the shoes removed by George from the prisoners' horses. Other evidence pointed to the guilt of the two prisoners. Bank of Australasia notes were found in Ballan's box, with serial numbers linking them to the dead banker. Searle had instructed his servant girl to state, if asked, that he went away at four o'clock and returned at six on the day of the murder - a blatant and provable lie. A constable, assisted by the native trackers, found in a paddock adjoining Searle's house two revolvers, wrapped in a piece of cloth and piece of paper. One of these was loaded in all the chambers but one. The balls were peculiar in that they were all less than the usual weight, by some eight grains, like the lead found in Mr Burke's head which was eight grains short weight.

After a couple weeks in custody Searle made a statement which enabled the police to go to the stable and find Burke's stolen gold buried. The gold found was within an ounce of that Mr Burke should have had in his possession at the time of his death and it contained some specific nuggets it was known Burke had purchased. Searle was hoping that his cooperation would see the charge of murder reduced because it was Ballan who had shot Burke.

At the trial in Ballarat, Morrissey gave evidence of some peculiarities in the shape of the horseshoes, and our relation George testified how he had taken two shoes off the black mare, and three off the bay, taking care not to take the nails out of the holes., and that the shoes produced in court were those that he had removed, "with the nails... clenched down and in the same position as when I removed them". Police witnesses gave extensive evidence testifying to the measurements and idiosyncrasies that had identified those shoes as the very source of the tracks followed by the trackers. That crime scene evidence and the other evidence left no room for doubt. The trial of Searle and Ballan for the murder of Mr Burke at Piggoreet was concluded when a verdict of wilful murder against the prisoners was returned. Searle and Ballan were hanged at the Ballarat Gaol on 7 August 1867 and buried in the grounds, in part as a result of our family member's contribution to early scientific crime scene investigation.

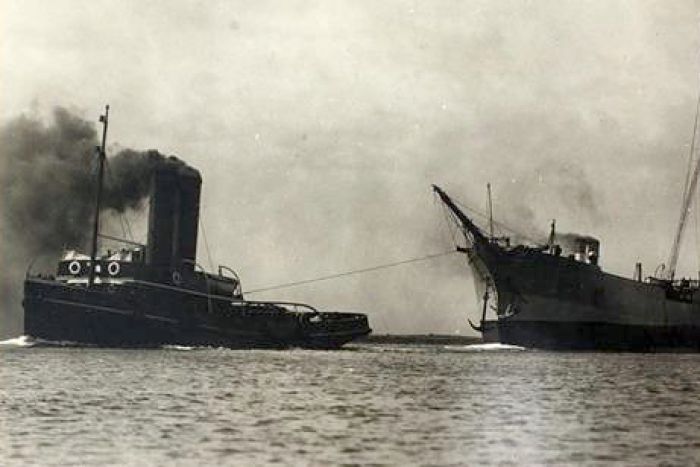

The Loss of the Steam Tug NyoraOn 9 July 1917, off Cape Jaffa, South Australia, the steam tug Nyora was towing the schooner Astoria, when it foundered with all hands. Among the 16 crew on the Nyora was cousin Sampson Henry Crocker, 48, a fireman on the tug. Miraculously the Captain and one crew member were picked up alive by the keepers of the lighthouse at Cape Jaffa, but 14 crew were lost. Sampson left a widow and six children. Sampson was the grandson of John and Mary Crocker, a farming family from Stroude, near Ermington, Devon, who had migrated to Hobart, Tasmania, with their seven children, aboard the Mary Anne in 1829. Some of the family had settled in Tasmania, some had gone on to New Zealand. Sampson's father had been the captain of a lighterman in Port Melbourne, Victoria. Sampson had been a fireman for Huddart Parker and Co., owners of the Nyora, for 16 years, and this was his second year on the tug. He had been a fireman on Huddart Parker's coastal trader Despatch when it sunk at Lake's Entrance in 1911, without injury to crew or passengers. In 1917 his eldest son Samuel was a Petty Officer on the armed yacht HMAS Sleuth. Nyora had been towing the Astoria from Port Pirie to Sydney; a four-masted American schooner with auxiliary steam power, but the auxiliary motor had broken down . On the morning of 9 July a gale was blowing. The tug was carrying forty tons of coal in bays on her deck, and it probably shifted in the gale. The huge sea smashed in the engine room door and flooded the engine room. The pumps were overwhelmed. These circumstances caused the tug to list. The crew cast off the tow hawser, and the tug moved off two miles to windward from the Astoria, but despite all, the Nyora foundered. With no power the Astoria could do nothing to help. They saw no signs of a lifeboat. The Astoria was later taken in tow by the steamer Yarra, and was towed to the safety of Guichen Bay. The Nyora had only been launched 8 years earlier. and had been especially designed for heavy ocean towing and for fire and salvage service. She was described as one of the most powerful tugs in the Commonwealth (Australian) waters. The Marine Board that enquired into the disaster found that the loss was caused by the severe gale that had arisen on 9 July, with every care taken by the Master, and that no blame was attachable to anyone on board. Special reference was made by the Board to the brave conduct of the two lighthouse men in effecting the rescue of the two survivors.

More Tragic Accidents in the Family

|

"Things just seemed to go too wrong, too many times." *It is estimated that 20% of the population will experience suicidal feelings in their lifetime. 6.7% will take action to end their own lives. There are many reasons why people may try to kill themselves: perhaps to escape what they feel is an impossible situation; to relieve unbearable thoughts or feelings; or to relieve physical pain or incapacity. Their life may have become too difficult or hopeless because of external events like debts or insecurity, a relationship break-up or the symptoms of a mental health problem. These family members deserve our sympathy for the emotions, thoughts and agonies that drove them to their untimely ends. Those family members who took their own lives include;

There are many myths and prejudices attaching to suicide, one being

that if their mind is made up, there is little one can do to help

those with thoughts of self harm. But there may be ways that your help and intervention can save a life.

The Samaritans' site has some suggestions about how you can help

someone with suicidal thoughts.

* From one of comedian Tony Hancock's suicide

notes.

|

|

Adrian Bell & the FIRST Times Crossword

| My 3rd cousin, once removed, of the

Crediton Berry and Bellringer branch of my maternal family, Marjorie

Gibson, married a writer, Adrian Bell. Adrian was born in

Lancashire, grew up in London, and was educated at Uppingham

School in Rutland, where during the First World War, with all

the young masters serving at the Front, the elderly teachers

drafted in were unable to maintain discipline, and Adrian had a

tough time there. Afterwards poor health (he suffered from

headaches throughout his life), and his father's

stubbornness kept him from university. He had a strong desire to

be a poet. Despite this, he found himself instead being shoe-horned into

journalism. His father was the deputy editor of The

Observer, so Adrian worked in his father's office.

That unhappy "apprenticeship" ended after about a month and he

was happy to leave. But he pursued his poetry. Leading what was described as

a Bohemian life in Battersea, one day he happened upon a small ad in

the Daily Telegraph - a Suffolk farmer was advertising for a young man as a

farming apprentice for a year. The poet in Adrian heard the call of the

Suffolk countryside and he decided that he could manage the

farming that went with it. Farmer Savage agreed to take him on,

perhaps with some reluctance, as Adrian's father had to pay

rather more than he expected to recompense the farmer for Adrian's obvious

lack of an agricultural labourer's physique. In any event, the

1921 census finds Adrian Bell at Great Lodge, Hundon, Suffolk,

his occupation "Farm Pupil" living with farmer Victor

Savage and his wife Martha. He took to the life, and could see

that he had found his vocation. After his apprenticeship

he bought a small farm, and started farming on a modest

scale, helped by his family. There were

obstacles to overcome. He was not skilled at the financial

aspects of farming. And this was a time of the Great Slump. Eventually economic conditions put an end

to his own farm. Living with his mother in Sudbury instead of

working on his own farm still, he began writing a fictionalised account of his

experience as the farm pupil, which became his first books -

the trilogy Corduroy (1930), Silver

Ley (1931) and The Cherry Tree (1932), describing life on the land in East Anglia.

He was encouraged by his friend, the poet Edmund Blunden.

It was in 1929 that his father was lunching with a friend from

the Times, who was bemoaning the fact that the Times was

losing readers, attracted to other quality dailies by the new

craze copied from American newspapers where it was a popular feature -

the crossword. Though Adrian had no experience or interest in

such a thing, his father assured his friend that his son could

create crosswords for the Times. Perhaps the three guinea fee

was too much of a temptation, for Adrian took on the challenge, and

compiled the first ever Times crossword, that was published in

the Sports Pages of the Times on 1 February 1930. It is said

that his crosswords were the first to feature cryptic clues.

The newspaper became an avid client for his puzzles.

At about the same time, when visiting his father, who was staying with Adrian's Aunt Mabel in London, he met a boarder there - our cousin Marjorie Gibson. She had been born in South Africa, the daughter of Lieutenant Gibson, a bandmaster in the Life Guard, and cousin Alice Bellringer. Marjorie was working as a secretary in London and had found lodgings with Aunt Mabel in Pimlico. Adrian was smitten. But before he could propose, to his dismay she was sent to stay with her aunt in the USA . When she returned in 1930 Adrian proposed and they were married at the earliest opportunity, in January 1931. Perhaps to their surprise, Adrian's novels were proving to be very successful, though the couple lived in often very basic, but perhaps to them romantic, dwellings. Continuing to write books, he also worked as a freelance journalist despite his adolescent misgivings about that role. But his ability to engage his readers with his perspective on farming and rural affairs proved very popular, in his periodical and newspaper pieces as well as his books. Adrian and Marjorie settled into married life, and began to raise a family, living in several rural settings and eventually returning to Suffolk, all the while Adrian writing his books portraying rural England. Even after the outbreak of war publishers could justify printing Adrian Bell's new titles, despite the shortage of paper. For despite the dark days that many servicemen suffered, Adrian's writings apparently brought rays of sunshine into their lives. He began to receive letters from soldiers on the front who had been obliged to abandon many of their possessions, yet somehow managed to retain their heavily thumbed copies of Corduroy, or some other Bell work, that summoned vivid memories of England's countryside. And POWs in the camps in Italy and in Germany wrote to him to tell how precious his writings were to them in their bleak surroundings. In 1943, when a local farmer was threatened with eviction as his farm was failing, Adrian bought the farm, and agreed that he should farm it, but allow the threatened farmer to stay on and help. By then it was 15 years since he had farmed, and he didn't see eye to eye with the previous owner regarding the best way to farm. But in wartime Britain farms worked to demanding standards and he was conscious that his predecessor had rather let things slide to a run-down state. There was plenty of help available to him as Italian and German prisoners-of-war were sent to work on the farm, and of course, Land Army girls. It took Adrian a while to reacclimatise himself to farming. And his mind inevitably was also on his writing and his crossword compilation. Determined to follow his more traditional approach, he did make mistakes. But he got through the war as master of his own farm. After the war he lost the help of Land Army and POWs. The Post-War years brought poor harvests, ill-health and a need for more income than the farm could generate, so in October 1949 he sold it. In 1950 he was contracted to write a weekly article for the local paper, the Eastern Daily Press. His crossword work continued, and he was still writing his novels. But the world became a different place in the 50s. Adrian's rural England was not so popular in the modern world. His books sold, but not in the numbers of previous years, and publishers were reluctant to take them. But he continued to have books published until 1976, achieving 22 titles, plus a volume of poems, and an anthology of others' writings that he edited. He continued with his weekly articles for the Eastern Daily Press, and continued compiling crosswords for The Times - almost 5000 of them in total. He died on 5 September 1980. Marjorie died in 1991. |

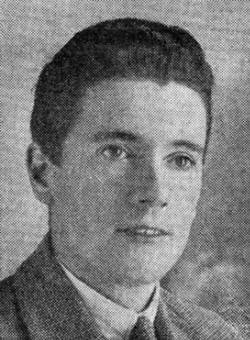

Adrian Hanbury Bell

The first Times crossword compiled by Adrian Bell in 1930.  Adrian & Marjorie. |

Sister Mary Oliva C.S.M

Agnes Oliva Willing

In 1919 Agnes was sent to Cape Mount, Liberia. She was based at the

Bethany School there, with 15 teenaged boarders and about 100 day

pupils. As well as teaching at the school, and teaching small classes

of infants in more distant communities, she had to preach at

missionary meetings in the local village. It was very much

training on the job, as Agnes was obliged to manage circumstances as

she encountered them, helped by locals and the other missionaries.

She learned something of the local Vai dialect, made journeys into

forest and bush to distant villages, and even to neighbouring Sierra

Leone, a journey of several days on foot and by boat. After a while ,

despite her misgivings about her medical skills, Agnes was obliged to

take over the running of the hospital and the dispensary for a while,

averaging only two bed cases, but with up to 5o dispensary cases

daily. Patients included everything from bad teeth to a woman with

leprosy who was isolated in a nearby field hut. For three

months, with some missionaries on leave and others moving to new

posts, Agnes was the only missionary on the station. During this

period she confronted the hostile opposition of a charismatic

revivalist sect, luckily without suffering the threatened violence.

Her absent colleagues returned, and in December 1921 Agnes left the

mission post and Liberia. She was suffering from malaria and on the

verge of a nervous breakdown. She sailed back to England on the SS

Bodnant, arriving in Liverpool on 31 December 1921. She stayed

with friends, the Bakers, in Upper Norwood for some 5 weeks before

sailing back to the USA on the SS Cedric. She settled in the

Deaconess House in Philadelphia, and decided then that she wanted to

dedicate herself to the religious life. At first she sought to be set

apart as a deaconess.

Sister Mary Oliva

Nenana was a native American community with a mission station and four missionaries. There were 30 boys and girls from age five to 17 years. In the early years she was teaching, but later she became assistant housekeeper. Her time there included confronting the kind of issues that one might expect in a disadvantaged community - petty theft, sexual and domestic assault, prostitution, drunkenness, an influenza epidemic. The native Americans were appreciative of the support the missionaries brought to their community, and they were happy to learn from the Gospel teaching. They brought beautiful beadwork, berries and dried fish to the mission every week, exchanging them for much-needed clothing. Agnes finished her term there in 1926, returning to the States by riverboat.

Agnes pursued her vocation further by becoming a nun, entering the novitiate of the Convent of the Community of St Mary, Peekskill, New York in November 1926, and being received into the Order on 21 September 1929, as Sister Mary Oliva. She was sent to Sagada in the Philippines in 1936., to resume her missionary work.

The mission worked with the Igorot tribes in the mountains. As well as teaching the youngest children, by 1837 Sister Mary and the other nuns were asked to teach the sacred studies to the High School students. She wrote that things in the mission had gone fairly smoothly, until the Japanese attacked the USA, and occupied the Philippines. The Sisters were taken into Japanese internment in May 1942, and were imprisoned at first at the former police barracks at Camp Holmes near Baguio. Agnes was philosophical about her internment. The missionaries suffered the hardships of deprivation of freedoms, food, company, communication with the outside world, but Agnes claimed that it was an opportunity for her spiritual and intellectual growth, having time to study. They endured cockroach infestations, and flooded quarters when the rains came. But the missionaries did not suffer the brutality that was inflicted on military and other prisoners. Space was at a premium in the overcrowded quarters, but at Baguio the Japanese allowed the American civilian internees take charge of the daily running of the camp. At first the sexes were separated which was hard on the families, and the crowding and constant presence of so many internees preyed on the nerves, and the screaming and crying of children was wearing. As the time passed, food rations shrunk, and daily life grew harder as the Japanese began to evidently be losing the war; they became edgy and more repressive. Then on December 29, 1944 the women and children were ordered to assemble before being put on trucks. The local Igorots feared the worse for their friends. But in fact they were transported to Manila, where they were interned in the Bilibid prison. The conditions there were filthy and disease ridden. There was little food in Manila, and the internees made do with rotten vegetables and mouldy corn. At first they removed the weevils from the corn, but then realised they were the only protein they were likely to receive, so they left them in. Within a week several internees including some of the sisters were sick with dengue fever. Then they discovered the water was poisoned. The men had to dig several wells to get access to safe water, though it could not be drunk without first being boiled. But Sister Mary seems to have endured all hardships stoically, strengthened by her Faith.

The end of Japanese occupation came suddenly, the Japanese guards filing silently out of the

prison, and in no time American tanks were rolling through the city.

There were major changes for the internees - much more and better

food, and the opportunity to leave the prison with a pass. But

internees of a sort they remained, and the war continued, with snipers

active in the city. Rumours that Bilibid was to be bombed caused

the women and children to be evacuated to a shoe factory for a day.

When they returned to Bilibid what meagre possessions they owned had

been looted by the Fillipinos. They continues saying Masses whilst

outside mortars dropped, and the sound of machine guns could be heard.

One morning a bomb dropped very near their end of the building, but the

Sisters survived. Soon they were moved to a camp at Santo Tomas

University. A few days later their repatriation began. They

boarded the S.S.Ebberle, and landed at San Pedro, California on May 2

1945. Sister Mary Oliva's account of her internment can be

downloaded here.

![]()

In 1946 Sister Mary Oliva returned to missionary work at Sagada.

The Convent and the Church had been reduced to rubble. War had

taken its toll of the Igorots, and the Sisters were asked to open an

orphanage. Many of the children were badly malnourished, and it took a

year before they began to recover. The Sisters resumed their High

School teaching, their work with the Women's Auxiliary Group and

training the Sisterhood of St Mary the Virgin.

Sister Mary Oliva's

foreign missionary work ended in 1957. She retired to the convent at

Peekskill, New York, where she continued with convent duties until her

death at age 92, in 1982. Her ashes are interred in St Mary's Convent

cemetery.

|

|

|

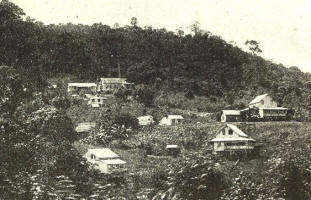

| The House of Bethany, school and mission, Liberia | Native village and mission, Nenana, Alaska | POWs at Bilibid camp, Manila |

Many thanks to Adrian Radcliffe for his help with the story of Sister Mary Oliva

Page updated 07/04/2024

© Nick Heard 2024